Opposing Forces in Crisis - How to Deal with Paradoxes

In a crisis one will face multiple challenges. A lot of these challenges present themselves as paradoxes. But what is a paradox?

Most people reading this article will have heard or read the word somewhere before. But to make sure we are all on the same page, we will examine the Cambridge Dictionary definition of the word paradox.

“a situation or statement that seems impossible or is difficult to understand because it contains two opposite facts or characteristics” – Cambridge Dictionary

A crisis per se is a difficult or often a seemingly impossible situation. But what do you do if additionally, you come upon a paradoxical problem - a problem that has two opposite forces? If you solve one side of the problem, the other gets worse and vice versa. What do you do then? Isn’t this hopeless? In my experience you can always find a solution to a paradoxical problem. The hint is already in the definition, as a paradox “seems impossible”. Usually, it will require outside the box thinking to find a solution. There are many tools and tricks you can use to think outside the box; processes that help you go through this.

The solvability of a paradoxical problem falls and stands with its definition. Some problems seem paradoxical, but when you get to the core of them, they are not any longer. By defining the paradox at hand first, you set yourself up better to find a solution to it. In some cases the solution is a trade-off, where you cannot solve the problem “perfectly”. You either choose one opposing force or you go with a compromise. In some cases you will be able to find a win-win solution. To sum up you can either:

Look for a win-win solution

Go for a compromise

Or prioritise one of the forces

Crisis in itself is usually also a very unique scenario dependent on shareholders, industry, stakeholders etc, coupled with a huge amount of stress. You might think that a paradox is the last thing you may want to encounter. But fret not, the good news is that from solving paradoxes the outcome is usually innovation and disruption. Paradoxes are hard to solve for, which means that not many try to do so. This is true for win-win solutions, if you prioritize or find a compromise to solve your predicament, then you are usually going for a “quick-fix” (there is nothing wrong with it, it is always down to priorities of problems and your goals).

Universal Rules of Thumb for Solving Paradoxes

Simplicity is king. Often people look for complex solutions, as we associate complexity with quality, while in reality the simpler a solution the better. Paradoxes are in essence quite simple by themselves. You have 2 forces that are opposing each other. Therefore, we can say that a paradox is two opposing problems and you should solve both. Below we will explore some simple rules of thumb to help you solve paradoxes.

Embrace Paradoxes

This may be a given, but often your first instinct would be to not accept a paradox. Make sure that you acknowledge paradoxes as a possibility and that they exist. Go even further and fully embrace them, own them, make them yours. Only once you have that mindset right, you will have the proper environment for creativity to spur. In his book “Creativity: Flow and Psychology of Discovery and Invention” Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi explains that creative individuals accept that they have paradoxes within them. Have you ever wondered how you can be at times an incredibly achieving individual, but at other times right out lazy? Or sometimes you are highly structured in your work and at other times you are completely immersed in chaos? These are the paradoxes within you and only by accepting these and using them, will you harness their full power. The same applies to an organization and to your employees.

Accept The Existence of Win-Win Solutions

When you have embraced the paradoxes, the next step is to accept that there can be a win-win situation or solution to a paradox. This generally will require in depth analysis through empathy, reframing of the paradox and concrete problem definition followed by creative problem solving. If you want to know more in detail on this, please explore my previous article on Design Thinking in crisis.

A typical paradox that we encounter regularly in our live is the following: To increase the quality on something you need to spend more time on it. But at the same time, the less time you have the more work you will get done in a shorter time (Parkinson’s law). The flow state is a win-win solution to this paradox. By the right amount of stress we are able to get into a state of flow, which will lead to a higher quantity and quality in the work we produce. Similarly, there are solutions to many paradoxes that will solve both opposing forces.

Define the Problem Properly

A famous example for defining the problem is the two sisters who are fighting over an orange. Susanne and Chloe both want the last orange that their mother has. What would you do as mother? If you decide to give the orange to one of them, there will be drama. This means, that you can only give the orange to both. But there will be even more drama, if they must split the orange themselves. So, you decided to cut the orange in half and give each one half. Both the girls are disappointed. Later you see that Susanne ate the inside and threw the peel away, while Cloe is using the peel to play and the inside is lying in a corner. By empathising with the two sisters at the start and understanding the problem, you would have been able to define the problem better. The solution would have been more obvious. We are far too fast to assume we understand, where in reality we do not.

Perseverance – Explore Different Paths

Often your first attempt to solve a paradoxical problem is not successful; or your second or even third and so on. Here the concept of perseverance comes in. Keep trying. If one path doesn’t work, try another. Remember if you cannot move a boulder that is blocking your path, then just walk around it and stop trying to move it or bang your head on it till it hopefully breaks (this is the slight difference between perseverance and persistence).

Types of Paradoxes in a Crisis

What type of paradoxes will you encounter in a crisis? Is there a possibility to group them in any way? Or can we form universal rules for different types to help dealing with them?

First of all, we should look at what competences are needed in a crisis and what defines a crisis. So, on the one hand we have characteristics of a crisis and on the other hand there are certain requirements to solve a crisis. As mentioned earlier a crisis is highly unique, but on an overarching principle every crisis is similar. The table below lists requirements and characteristics of a crisis. This table is not to be understood as complete, more like a work in progress. If you can think of any more characteristics and requirements that come to mind, please add them for yourself, or even better add them in the comment below, so I can learn from your insights too.

Many of the listed requirements and characteristics can in combination form paradoxes that you may encounter in a crisis. Most of the paradoxes are paradoxes that come from a requirement and a characteristic standing opposite to each other. Some paradoxes are formed from requirements standing in paradox (RR) to each other or characteristics standing in paradox (CC) to each other.

This gives us three groups:

Requirement vs Characteristic (RC) Paradoxes

Requirement vs Requirement (RR) Paradoxes

Characteristic vs Characteristic (CC) Paradoxes

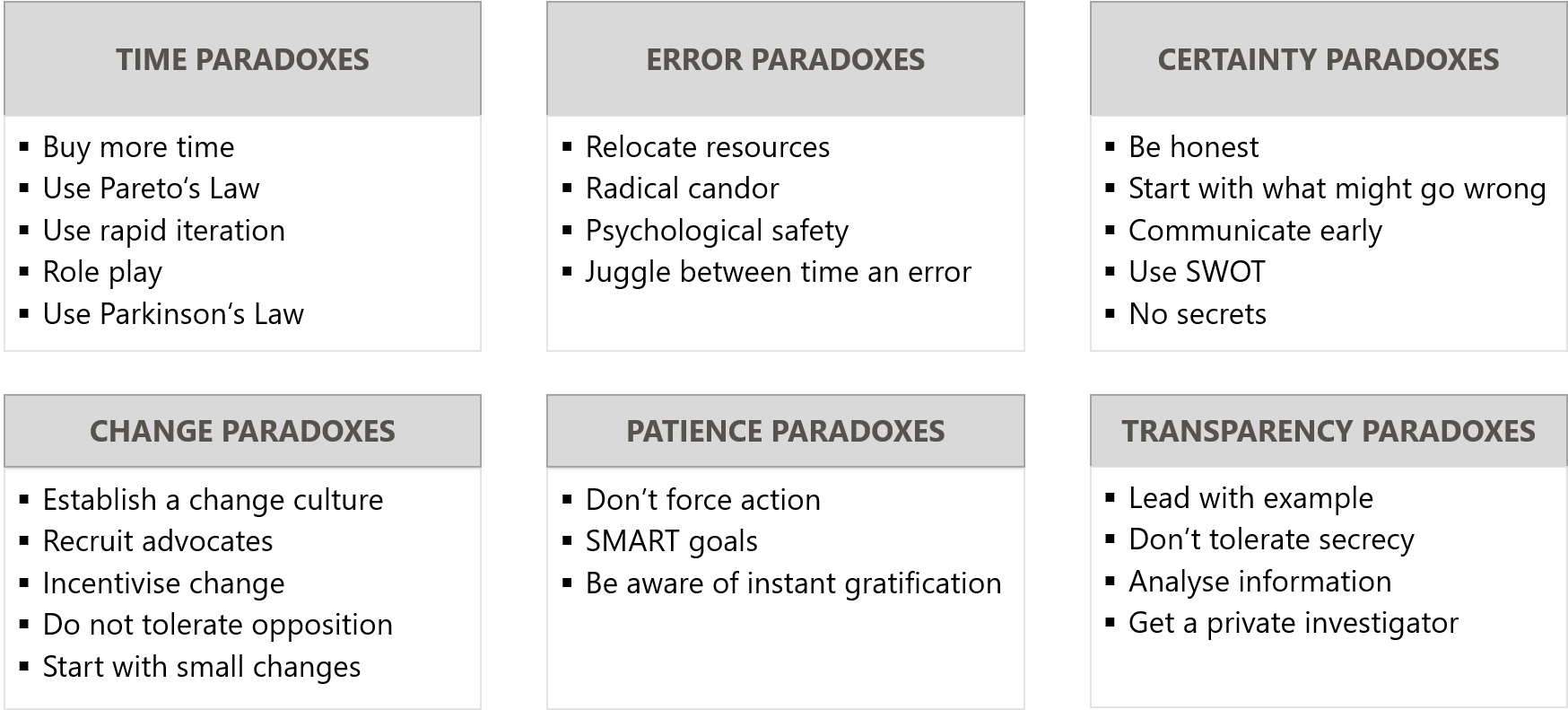

These groups create quite a large list of paradoxes. Again, this list is not to be understood as complete, it is rather more of an overview for the mountain of possibilities. The list is at the end of the article. If you have the time and want to put the effort in, you can study it in detail. From this list as a basis, we can form 6 overarching groups.

These 6 groups give a good overview of the issues that we tend to face in a crisis. Every crisis will have you face a shortage of time, a little error margin, a lack of certainty, the need for change, the need for patience in carrying out measures and a need for transparency to solve effectively. Some of the biggest challenges are pictured by these groups and their paradoxes. At the same time each group has a few universal measures you can take to help you solve them.

Time Paradoxes

Anything that forms a paradox with the characteristic of “not much time” goes into this group. Time is one of the main challenges you will face in a crisis. A lack of time is nearly always a problem. We humans tend to realise too late that we have a problem. Or let’s put it this way, if we were to realise early enough, we would find ourselves in the area of risk mitigation. There are also instances where the problems were seen before, but nobody acted on them. But usually a crisis is a somewhat surprising event.

If you are the crisis manager, you will have a bunch of acters pressure you and require fast action. Stakeholders, shareholders, employees etc. want to have a quick solution to the crisis. Considering the “Time, Resource and Quality” triangle we can see that if you want a fast solution you will need a lot of resources for it to be of quality. If you end up taking down quality, you will have a fast and cheap solution. Obviously, there are exceptions to this triangle (for example Parkinson’s law as mentioned earlier). I like to use this triangle to evaluate which consultants I chose for a certain task.

In general, the most prominent paradox in a crisis is the Time and Error Paradox CC1, which arises from the simultaneous presence of the need for speed and a low error margin. While you are pressed for time and need to act fast, you are at the same time confronted with a low tolerance for error. But if you increase the speed usually the chances of error increase. This situation leads to a high amount of pressure on everyone involved and is very difficult to handle.

When looking at the list of requirements to solve a crisis we can see that most of them form a paradox with time. Which shows us, that time is of incredible importance.

So, what are a few overarching concepts that can help us managing our time issues?

1. First try to buy more time. You will be surprised of how, by just being open and honest about your problems you can buy time. Often your business partners or policy makers are dependent on your success. You failing will entail some problems for them too. Humbleness is of the essence. Do not get arrogant or play the blame game. Instead own the crisis “Complete Ownership”-style.

2. Use Pareto’s law as much as possible. Focus on the wildly important. People will bring a multitude of problems to you in a crisis as everyone is in a problem mindset and will find lots of problems at every corner. Make sure you focus on the most important issues.

3. Define problems well. It may seem paradoxical but especially when defining your problems at the start you should take a bit of extra time. This will make sure that you do not run of in the wrong direction or focus on the wrong issues.

4. Use rapid iteration. This is used in product design quite frequently. Do not ponder too much on your solutions, quickly move on and go forth and back in the process. Do not be scared to admit that a solution you went after is not working and you need to go back to the drawing board.

5. Use role play to play through solutions before starting to incorporate them. This is a quick and easy way to experiment with solutions, especially if they involve human interaction (for example with policy makers).

6. Use Parkinson’s law to your advantage. By looking at the stress performance curve there is an optimum amount of stress for us to produce our best work. Try to see where more pressure can lead to better results. But be careful not to overdo it, as this can cost you. More on this in my recent article about self management.

Error Paradoxes

Crises are very emotional, but the room for error is little. Nervousness, angst, sadness, anger are just some of the emotions you will have to deal with. Unfortunately, emotions cloud judgement and lead to bad decisions. Furthermore, being emotional results into a lack of concentration. On top of that, having little room for error leads to higher pressure by itself and thus to even more emotionally charged situation. Any processes like rapid iteration, brainstorming, prototyping etc. need errors to occur. We make errors and from each error edge closer to the solution. We live in a failure adverse society, which can hinder innovation and creativity. We do not have to find errors great and celebrate them. Let’s be honest, failure is painful and you do not want it. But it happens and its important to reflect on it and use it to your advantage. In crisis we need solutions fast, and this will lead to errors occurring. Fear of them will cost you speed and resources, which are both usually scarce.

1. Reallocate resources frequently. By looking at your workforce and what is being done, you can smartly reallocate resources to where they are needed the most. By doing so you can increase the error margin, as more resources will allow for more errors. This is a dynamic game, so you might have to reallocate resources frequently. In the best case you introduce a crisis taskforce, which works on whatever issue is the most pressing.

2. Radical candour within the organization is important. Errors need to be called out quickly. At least if you do make errors, acknowledge them quickly and correct them. This is enormously important for rapid iteration.

3. Create psychological safety within your organization. When your team has the feeling they are working and acting in a safe environment, they are more motivated and honest. Honesty means that people are quick to admit mistakes. A culture where people feel afraid to fail, means they hide errors or are not willing to take risky and uncertain actions. Uncertainty is a huge part of a crisis as we will see later. You could try to already set up possibilities for your team to move into new jobs if things shouldn’t work out. This will serve as a safety net.

4. As the “Time and Error Paradox” is one of the most prevailing paradoxes and all requirements to solve a crisis build a paradox with one or the other, it is important to juggle between them. If you manage to get more time you can make more errors, but if time is starting to run out, play it a bit safer. If time is of the essence it is better to have an OK solution and get it in place, than to work on an amazing one and not get it done in time. Crisis can be an all or nothing game, so play accordingly.

Certainty Paradoxes

Quite a few paradoxes are formed around the notion of certainty (requirement and characteristic “Human need of certainty”) and uncertainty (characteristics). Un-/Certainty is a very tricky topic as it leads to three CC and two RR paradoxes. Certainty or let us say the “sense of certainty” is a vital component in conquering a crisis. Most people involved will long a sense of certainty, as this is something most humans long for. Your investors need a sense of certainty so that they have the trust, that you will get through the crisis. The same goes for your share- and stakeholders. In a crisis you want all parties involved to work together for a solution. But when uncertainty takes hold, it may end in everyone fighting for their own agendas, which can cause complete destruction and chaos. Moreover, a crisis is per se already a very uncertain situation. So paradoxically you want to try and convey a sense of certainty.

Many decisions we make in uncertain situations stem from our gut and often are snap second decisions. These are very hard to explain but are necessary as often the data to form a conscious and well-argued decision just is not there. To get out of a crisis we have to explore new paths, that no one has walked before (be it the industry, family or organization). Again, walking unknown paths is uncertain.

What should we focus on to solve certainty paradoxes then?

1. We have had it before, but honesty and radical candour are really important. Your team and stakeholders are looking to you to lead out of the crisis. By being honest you will instate certainty. No lies, or misinforming, as this will add to uncertainty.

2. Communication is key. Especially when you decide that you are walking a new path. Counterintuitively it is even more important to communicate what could go wrong and to do this first. Studies have shown, that in investor pitches for example your chances of success increase if you start of with telling investors why they should not invest. By doing this you create a sense of certainty, as the worst possible outcomes are already out on the table. From there on, there is more room to focus on what could be and how to mitigate those risks and uncertainties. By listing the problems, team members and stakeholders etc. will not need to think about what could go wrong. You can get them into a problem-solving mindset. Never underestimate the power of the negativity bias, we are poled to look for the negative by nature.

3. Make sure to communicate early. Whenever there is a problem or any good news, be quick to convey it. The worst that can happen is that people receive bad news from third parties and often the “news” will have been warped. This will cost you a lot of energy and time to undo. Better be upfront and be upfront quickly. Early communication increases the speed and increases trust levels.

4. Change in the environment leads to uncertainty. A very old but gold tool can help you with this and it is a SWOT analysis. By showing that there are new opportunities in the changes you can decrease the amount of uncertainty the alterations bring with them.

5. Use back up plans when applicable. Having a plan B is generally a good idea. There is a lot of disagreement on this thou. Arnold Schwarzenegger, for example, said in a famous interview that “Plan B sucks”, as it takes away resources and commitment from Plan A. This is to some degree true. A plan B can reduce focus and commitment from you and your team. On the other hand, your stakeholders love a good plan B to generate certainty for them. I suggest that it is worth while to divert a very small amount of time and resources to have a rough idea of a plan B in place. I would say 95/5, so 95% on plan A and 5% on plan B and do not have the whole team work on plan B, maybe designate one person to it.

Change Paradoxes

Change is a requirement and a characteristic. Most crises require change, but at the same time a crisis is brought about by change; be it change in the leadership, change in the business environment, change in customers or suppliers etc. We talked about psychological safety above, and for most people to feel save they need certainty. The need for certainty leads to an over evaluation of tradition and “hate” for change.

Two of the “Change Paradoxes” are formed with characteristics (tradition and need for certainty) and are especially fatal. The changing environment calls for people to change, but at the same time they are reluctant to change. Big corporations or old family businesses are especially vulnerable to this dynamic. At the same time the changing environment leads to uncertainty. When people have the feeling that things are not under control, they will get nervous and start to follow their own agendas. If you however manage to instil a feeling of togetherness and control, you can make the team get closer and work out the problems.

The number of RC paradoxes in the table shows just how many opposing factors to change you will encounter during a crisis. Change in any structure (family, organization, team etc.) will require time and resources, which are both usually scarce in a crisis. Change also usually means uncertainty, which will pose an issue, as humans wish for certainty. It would be counterintuitive for most to do things, which will increase uncertainty, rather than decrease.

1. Change requires time, so as already stated, try to buy time wherever you can.

2. Make sure that everyone understands that change is needed to get through the crisis. Also make sure people will feel that change means more certainty. Explain that no change means certain “death”, while change offers a chance. Really try to establish a change culture.

3. “Recruit” individuals to help you advocate for the change. Be it friends of the patriarch, or any employees who are eager to change, or partners, suppliers, customers. The fastest way to get people to follow you into change is by having people whose opinions are trusted support you.

4. Incentivise ideas or actions for change in the team. But don’t start throwing around with bonuses. Try intrinsic motivation rather than extrinsic and make sure you praise people for ideas and actions on change.

5. Don’t tolerate people, who slow down or oppose the change process. If you cannot get team members - lawyer, tax advisor, sales manager or the cleaning team - on bord, part ways with them asap. Keep in mind: sometimes this is not possible. For example, if it is the patriarch. You will have to move around it somehow.

6. Big change starts with small change. Start with moving people around in teams, change offices, change who sits where or even change responsibilities, how you spent your financial resources (every cent you can safe is worth saving). You want every employee to be on bord in using existing resources to the maximum. You never know how tight things can get. It starts in the small.

Patience Paradoxes

Patience is a key ingredient in solving anything. Especially in a crisis it will often seem misplaced to have patience, since correcting action is required fast. This is a very common paradox you will face, the need/urge for action against having patience. Having patience is not the same as sticking your head in the sand and hoping for the best. If you have put measures and actions in place and need to wait for them to work and show their outcome, give them the time to do so. Do not rush things, that are not in your control. A typical example would be if you have a court case and the judge needs time to form a decision. By bothering the judge you might actually influence the outcome negatively.

What are the universal rules when it comes to patience paradoxes?

1. Don’t force action. While you are waiting for your actions and decisions to unfold and hopefully bring your intended outcomes, it can help to write down all the things that can happen. This can calm you and bring a sense of certainty to yourself (as it works with stakeholders as shown above, it works with yourself). This can keep your monkey mind busy.

2. Use SMART Goals. By dividing large goals into smaller sub goals that are well defined you will have a set yourself upon a good path to follow. By working at one small goal after the other, you will see your progress and it calms you. Often if we just start with our stretch goals (like solving a crisis), we get anxious, because the achievements seem incredibly minute in comparison. More on SMART Goals here.

3. Be aware of instant gratification and our human “need” for it. One of the main neurological and psychological drivers for us to be impatient is the need for instant gratification. Do not let this sway you off your path. Especially when planning strategically and planning long term goals, there will not be any short-term success. Do not let the urge for a short-term gratification endanger your long-term goals. One easy way to trick your mind is to plan instant gratification into your processes. A typical example would be that when reaching a smaller milestone in planning you invite the team for dinner. This way everyone gets a reward, even though the actual outcomes of your planning have not taken effect yet.

Transparency Paradoxes

We have covered secrecy and transparency quite a bit already in the other paradox groups. Which just shows that even the 6 groups have overlapping attributes and similarities in how to solve them.

In a crisis information is often not dispersed, dispersed slowly or disinformation is spread. Secrecy, lack of cooperation and over-processes can make a crisis worse. I have seen many family crises where the patriarch is the centre of all knowledge and no one else has the knowledge that he has. What happens when he is suddenly gone? The sudden death of the leader of an organization is often the reason for a crisis. Not only will competitors use it to their advantage. For example, your employees may claim that they always got an extra Christmas bonus in cash, but you have no way to confirm. What do you do then? Possibly break a tradition, or are they making it up? Politics and intrigues are the last things you need when you are in a crisis. Make sure that if they are part of your organization, that you get rid of them pretty quickly.

The main rules to solve transparency paradoxes are:

1. Lead with example, by being transparent and open for questions and explain your decisions and actions. If it is a gut feeling you are following, then tell them, simple as that. If you have thought about a decision thoroughly and came to a conclusion for certain reasons, communicate it.

2. At the same time do not tolerate secrecy. Make it clear that secrecy is not accepted in the organization any longer. And when you catch people doing it draw consequences. Even if an employee seems to be a “star” but indulges in secrecy a lot (often one of the reasons he is a star), you need to make him stop or get rid of him. Tolerating it harms the team more than losing a seemingly great performer.

3. Analyse information you have at hand carefully. People in your organization or stakeholders might try to hide things from you. Make sure you analyse information you have with that in mind. Often you will find clues that suggest for it. Getting blind sided in a crisis is very painful and can lead to total destruction. So be careful about this.

4. Last but not least one of my favourite learnings and suggestions is to get a private investigator. Depending on your situation it is important to trust your team and partners, because distrust slows you down. Trust is given and not earned. But if for any reason things have been done or seem to being done that warrant distrusting someone, get a PI to find out more. PIs are very good at finding information and analysing it, often we do not think of seemingly obvious explanations for behaviour or we do not build the puzzle accordingly. When we had our crisis a PI was of enormous help and in every other crisis I have managed till now information gathering was one of the keys. A PI can also act as an intermediary. Sometimes people will not feel comfortable talking to you at first and rather tell a third party. Use this to establish transparency.

A quick and handy overview

You will encounter paradoxes everywhere in life, also within yourself. In my opinion it is one of the most important skills in life, to be able to acknowledge, embrace and work with these paradoxes. I hope this article will help you to identify paradoxes in the future and to see how you can leverage them to your advantage instead of despairing over them. I also apologize for any missing paradoxes in the list or if in your opinion I have missed any requirements or characteristics. Please send me a message if you do miss something, I love the feedback!